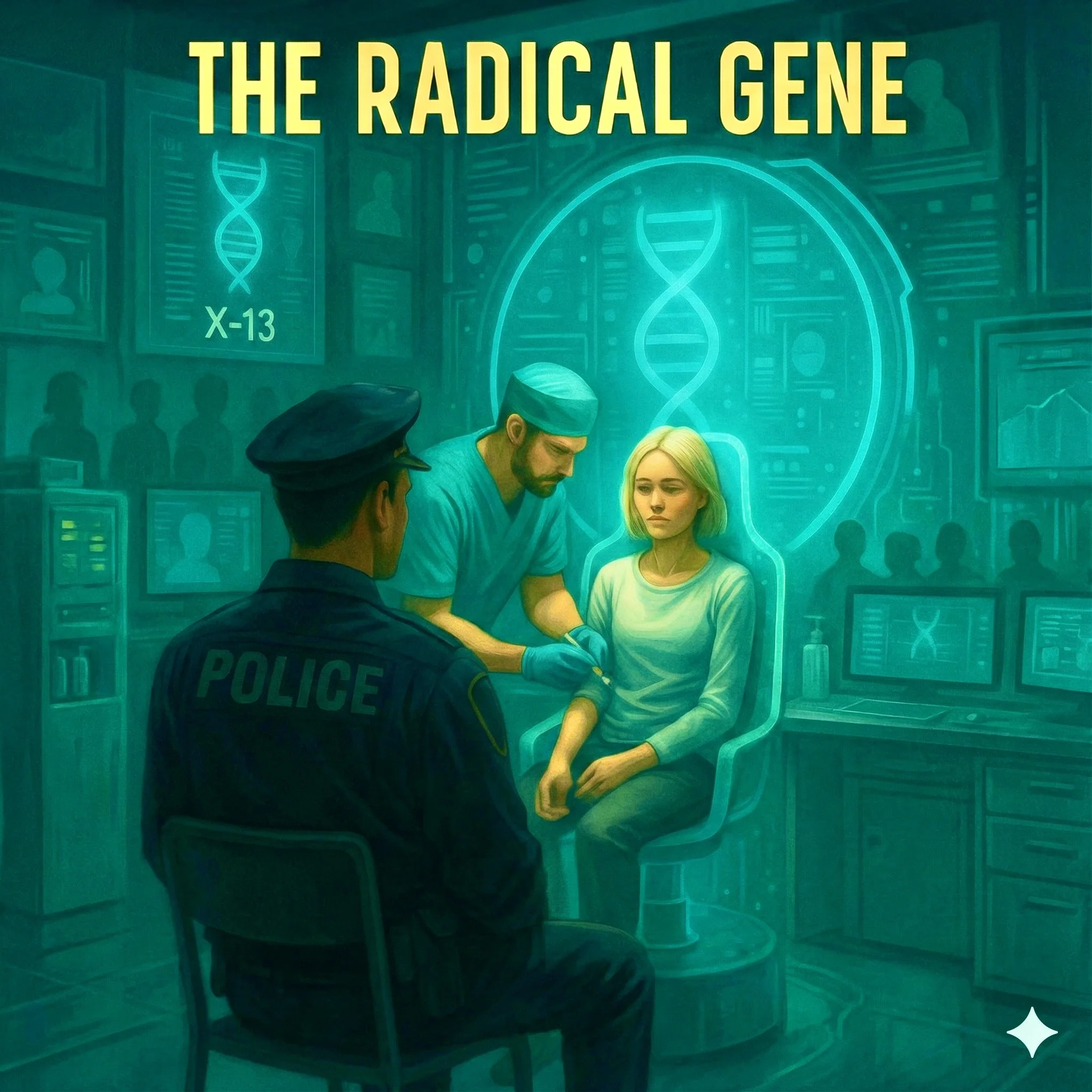

The Radical Gene

Every newborn tested. Every adult screened.

Can a society truly thrive when its citizens were cataloged by their DNA?

It began in 2025, with a question whispered across decades of tragedy: Why do lone-wolf extremists commit such senseless acts of violence? The truck attack in New Orleans. The fire in Boulder. The Grand Blanc church assault. The National Guard ambush in Washington, DC. Each one etched into memory as a symbol of chaos.

And then came the shooting at NFL headquarters in New York City, where the perpetrator left a note claiming he suffered from Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE). That was the spark. Researchers began to wonder: could extremism itself have biological roots?

Just as dementia is tied to genes like APOE and APP - and aggression linked to the MAOA “warrior gene” - might there be a hidden genetic marker — a precursor coded into the genome — that predisposes individuals to violent radicalization?

By 2032, the answer arrived. A team of geneticists announced the discovery of Variant X-13, a subtle mutation found in less than two percent of the population. Early studies revealed a chilling correlation: individuals carrying X-13 were statistically more likely to engage in violent, ideologically motivated acts. The science was controversial — but undeniable.

To test its implications, researchers partnered with an average American city: Midvale, population three hundred thousand. Every citizen was screened. Those carrying X-13 were quietly enrolled in intervention programs — counseling, conflict-resolution workshops, mindfulness training, and monitored community support. These programs were designed not only to guide behavior but to harness neuroplasticity, reshaping the very architecture of the adult brain. For decades, scientists believed such rewiring was limited to adolescence, but new evidence showed that targeted interventions could alter neural pathways well into adulthood, reducing aggression and strengthening empathy. Citizens were added to a registry, tracked not as criminals… but as potential risks.

The results stunned the nation. For twelve consecutive months, Midvale reported zero murders. Zero shootings. Zero vehicle-style attacks. A city once plagued by sporadic violence became a model of peace. Headlines called it “The Year Without Bloodshed.”

But peace came with shadows. By 2034, state legislatures began drafting laws: mandatory genetic testing at birth. Registries maintained by law enforcement. Programs enforced by statute. Citizens identified with X-13 were required to attend intervention sessions, their compliance monitored through biometric apps. Failure meant fines, restrictions, even confinement.

The public was torn. On one hand, the absence of mass killings was undeniable — a miracle in a country long haunted by gunfire and sirens. Parents slept easier. Schools stopped rehearsing lockdown drills. Stadiums filled without fear. For the first time in decades, the specter of terrorism seemed to fade.

Yet beneath that relief lay unease. The registry grew; privacy shrank. Citizens whispered about government overreach — about being branded at birth for crimes they might never commit. Some feared the slippery slope: today X-13… tomorrow another gene, another behavior deemed dangerous. Was this science serving the greater good, or the quiet rise of genetic authoritarianism?

In 2036, the program expanded nationwide. Every newborn tested. Every adult screened. The government promised compassion, not punishment. “We are not criminalizing biology,” officials declared. “We are preventing tragedy.” And indeed, the statistics glowed: mass killings plummeted. Extremist attacks nearly vanished.

But in living rooms and coffee shops across the country, the debate raged on. Was safety worth surrendering autonomy? Could a society truly thrive when its citizens were cataloged by their DNA?

Midvale remained the shining example—a city free of bloodshed. Yet its streets carried an invisible tension. People wondered who among them bore the marker… who lived under constant watch… who carried the burden of being seen as dangerous by design.

The discovery of X-13 had answered the question of why. But it left humanity facing a deeper one: At what cost does safety come?

Author’s Note

As I looked back on the year’s headlines, one unsettling pattern emerged: lone wolf extremists committing acts of senseless violence. The truck attack in New Orleans on January 1, the Molotov cocktail attack in Boulder on June 1, the Grand Blanc church assault on September 28, and the National Guard attack in Washington, DC on November 26 — all raised the same haunting question: why?

That question grew sharper after recalling another tragedy: the mass shooting at NFL headquarters in New York City on July 28. The shooter left behind a note claiming he suffered from Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE), a brain condition tied to confusion, aggression, depression, and even suicide among those with repeated head trauma, such as athletes and military veterans.

This link sparked a provocative idea: could extremism itself have biological roots? Just as dementia has been associated with genetic markers like APOE, APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2—and aggression with the MAOA “warrior gene” — might there be a genetic signature that predisposes individuals to violent radicalization? If so, an even more profound question arises: how should law enforcement respond if science one day identifies those at higher risk before tragedy strikes?

Discussion Questions

If genetic testing could prevent violent extremism, how should law enforcement balance public safety with individual privacy and civil liberties?

What safeguards would need to be in place to ensure that a genetic registry of “at‑risk” individuals is not abused or misused by law enforcement or other agencies?

How could law enforcement collaborate with mental health professionals to design intervention programs that leverage neuroplasticity, ensuring they are rehabilitative rather than punitive?

How might mandatory genetic testing and monitoring affect community trust in law enforcement, and what strategies could be used to maintain transparency and accountability?

If science identifies additional genetic markers linked to other behaviors (e.g., aggression, impulsivity), how should law enforcement decide where to draw the line between prevention and overreach?

About the Author

Craig T. Solgat is a Captain with the Metropolitan Police Department of Washington, DC.

He is also a published author whose work has appeared in numerous professional journals, contributing valuable insight on public safety, national security, and police leadership. To read his full bio, click here.

To download a printer-friendly version of the story, click here.