Adaptive Policing: A New Climate, A New Paradigm

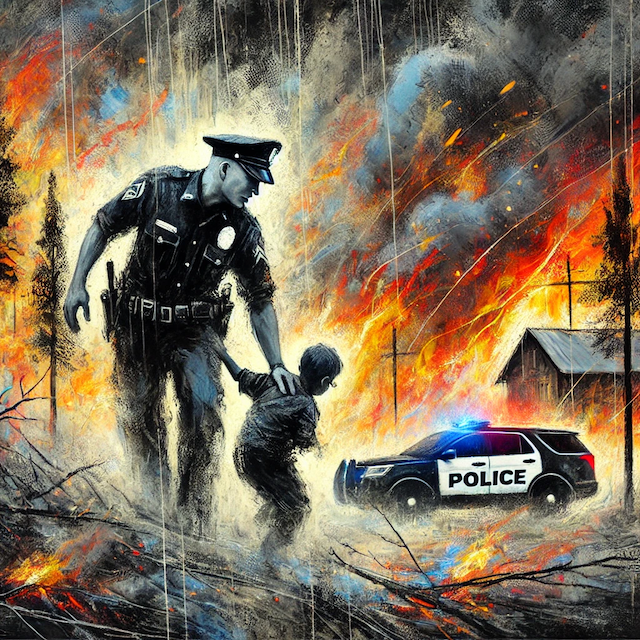

An officer’s beat is no longer just a set of city blocks threatened by crime; it is the ever-shifting perimeter of a wildfire, the debris field of a tornado, or the floodwaters consuming a town.

A Fictional Near Future

The crackle over the radio wasn't about a robbery in-progress or a high-speed pursuit. It was a sound Officer Maya Singh had come to dread more than any "shots fired" call. It was the sound of fire. A hungry, monstrous breathing that devoured acres of California hills and canyons with every gasp. Her beat wasn't a set of city blocks anymore; it was the ever-shifting, smoke-choked perimeter of the fire line.

From her patrol car, parked on a ridge overlooking the Pacific Coast, Los Angeles didn't glitter; it glowed an apocalyptic orange. Her job today wasn't to catch a cat burglar, but to convince a stubborn old man that his home of fifty years was about to become a pile of ash.

"Sir, we have to go," she'd pleaded, her voice hoarse. "The embers are already landing. This isn't a negotiation."

He had finally agreed, his eyes reflecting the flames that danced over the chaparral. As she drove him toward the evacuation center, she glanced in her rearview mirror. Her usual adversaries – the desperate, the defiant, the dangerous—had been replaced by an enemy that couldn't be reasoned with, couldn't be cuffed, couldn't be stopped. It could only be fled. The law was written for people, but the fire answered to no authority but the wind.

Months later, thousands of miles away, Trooper Cole Jackson stood where the town of Mayfield, Kentucky, used to be. The sky was a bruised purple-gray, the air thick with the smell of pine, rain, and ruin. A supercell had ripped through the landscape, and his training in accident reconstruction was useless here. The entire town was the accident scene. His partner wasn't another trooper, but a grim-faced woman from the search and rescue team, her golden retriever whining softly, eager to work.

"Anything?" Cole asked, his voice rough.

The woman shook her head, running a hand over the dog’s back. "Just…splinters."

They weren't looking for shell casings or fingerprints. They were listening for cries, for whimpers, for any sign of life beneath the mountains of debris that had once been homes, a church, a hardware store.

Cole had spent his career learning to read the tells of a liar, the flicker of guilt in a suspect’s eyes. Now, he was trying to read a landscape of chaos, looking for the impossible geometry of a survivor's pocket in the rubble. He saw a child's tricycle, its front wheel bent into a pretzel, and felt a cold dread that had nothing to do with crime statistics. This wasn't about good guys and bad guys. It was about the living and the dead.

In Arkansas, Deputy C.J. Miller navigated his flat-bottom boat through what was once the main street of a small farming town. The stop sign at the corner of Oak and Third was almost completely submerged, a small rectangle of red in a world of muddy brown. His shotgun was locked in its rack, useless. Tucked into his tactical vest were granola bars, bottles of water, and a first aid kit. He wasn't serving a warrant; he was a delivery service for the stranded.

A woman waved frantically from a second-story window, a baby in her arms. "We're on the roof!" she screamed over the churning water. "My husband's up there!"

Miller killed the engine and expertly guided the boat toward the house. This was the third family he’d pulled from the floodwaters today. The sheriff's office had two of these boats now, purchased after the last "hundred-year flood" that had happened just three years prior. His law enforcement academy training hadn't covered nautical knots or how to pull a terrified child from a rooftop into a moving boat. He and his fellow deputies were learning on the job, their patrol routes redrawn by the rising river. They were no longer just keepers of the peace; they were guardians against the water, their badges a small gleam of hope in the relentless, rising tide.

Making Sense of the Chaos: The Case for Adaptive Policing

The harrowing experiences of Officer Singh, Trooper Jackson, and Deputy Miller are not tales from a distant dystopia. While fictionalized, they represent a stark and growing reality for policing across the globe. An officer’s beat is no longer just a set of city blocks threatened by crime; it is the ever-shifting perimeter of a wildfire, the debris field of a tornado, or the floodwaters consuming a town. The scenes described above illustrate a fundamental challenge to the traditional role of policing, one for which most agencies are dangerously unprepared. Extreme weather events were rapidly becoming the norm. And as a result, policing must evolve and adapt to this new reality.

This evolution is best understood through the framework of adaptive policing. As detailed in the work of researchers Jarrett Blaustein, Clifford Shearing, and Maegan Miccelli, adaptive policing calls for a systemic shift in the mentality, function, and capabilities of police. It recognizes that in an age where human activity is destabilizing the planet – the 'Anthropocene' – the boundaries between "natural" and "social" order have dissolved. Police can no longer focus solely on human-instigated threats when the greatest dangers are emerging from our environment. This framework provides a critical lens through which to analyze the challenges faced by the officers in these stories, centered on three core concepts: absorption, adaptation, and transformation.

Absorption is the first line of defense – an agency's ability to withstand the initial shock of a crisis. It’s the capacity to manage immediate chaos without collapsing. But as the stories show, the scale of these disasters pushes police far beyond their standard operating procedures. Simple absorption is not enough when the threat is chronic and escalating.

This is why adaptation is essential. Adaptation is the process of learning from disasters and making incremental changes. It is what we see when Deputy Miller’s department in Arkansas, having faced repeated "hundred-year floods," purchases flat-bottom boats and retrains its deputies in water rescue. It is the curriculum change that must happen at academies to prepare future Officer Singhs for fire-line evacuations instead of just traffic stops. This process requires flexibility and a formal recognition that emergency management is now a core police competency, not an ancillary duty.

The deepest and most vital stage is transformation. This requires a fundamental reassessment of policing’s values, mandate, and identity. In the vignettes, the traditional "us vs. them" paradigm of law enforcement becomes meaningless. Trooper Jackson isn't facing a criminal; he's confronting the indiscriminate ruin of a tornado. The enemy cannot be arrested. This reality forces a shift toward an "ethos of care," where the priority is protecting all life and empowering vulnerable communities. A transformative approach means police see their role not merely as enforcers of the law, but as guardians of societal resilience. It means recognizing that true public safety is not just about the absence of crime, but the presence of stability and equity in the face of existential threats.

Of course, this evolution is not simple. The institutional culture of policing is often conservative, focused on maintaining the existing social order. This can create a paradox where police are tasked with protecting a society from the consequences of its own environmentally destructive habits. However, as the first responders on the scene, they have no choice but to confront the reality of this new, chaotic world.

The stories of Singh, Jackson, and Miller are therefore more than just dramatic fiction. They are illustrations of a crucial turning point. They make the academic concept of adaptive policing tangible, demonstrating that for policing to remain effective, legitimate, empathetic, and just, it must learn to police a new and profoundly more challenging beat.

To read the brief on the research by Blaustein et al click here.

Note: Dr. Jarrett Blaustein is an Associate Professor at The Australian National University, the founder of the Adaptive Policing Lab, and a Future Policing Institute Fellow.